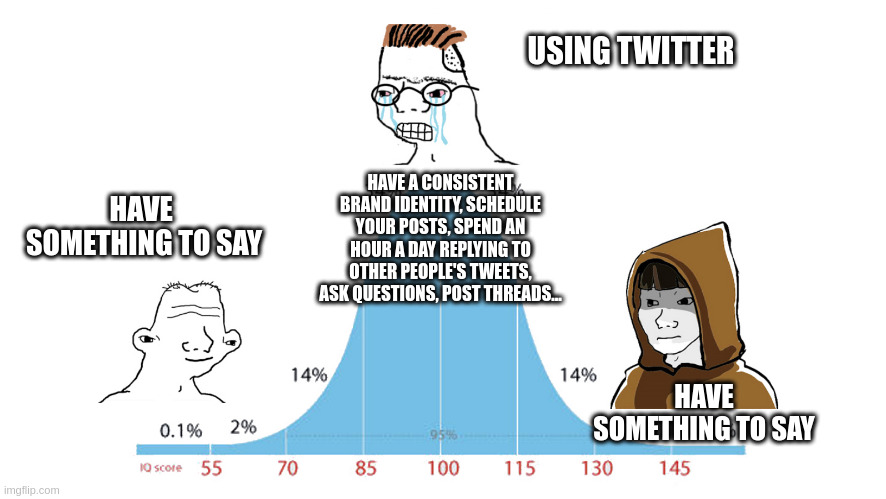

How I wish people used Twitter versus how they seem to be doing it lately.

I’m not quite sure when I started feeling uncomfortable with Twitter.

It wasn’t when Elon Musk bought it, or during the mass firings, or the bluecheck fiasco, or the rebrand to X, or any of the other politically-obvious times that many people decided to give up on it.

No, I was a Twitter optimist for a long time.

But somehow, somewhere over the last few months, my positive outlook on the platform has slowly eroded away. As I—ironically—spend as much time as ever scrolling through my feed—I find myself more and more annoyed, jealous, outraged, yes, but mostly just… bored.

And what’s funny is that the content is more “engaging” than ever. My feed is full of posts that have obviously had more effort put into it than most of what I used to see. Megathreads about AI, thoughtful, longform narratives that could have been blog posts, carefully curated images, and super-positive business updates. It’s mostly engaging stuff.

And therein, I think, lies the problem. The content I now see on Twitter is content that has been designed to be seen on Twitter. Tweeting has become a job. Quite literally, for many people, ever since they’ve started paying creators a share of ad revenue.

And yes, on the surface this incentivizes people to create better content. The better your content is, the more it gets seen, and the more money you make. And yet, my felt experience of this change is the exact opposite—as people seek more engagement, their content gets worse. What’s going on here?

One possibility is that I am unusual. I go on Twitter for authenticity. I have carefully curated a list of human beings who I know by name, and whose ideas and actions interest me. But authenticity is often at odds with growth.

Why? Well to grow you need to be noticed. To be noticed, you need to stand out. And to stand out is—usually—inauthentic.

Yes, we all say and do noteworthy things, but not every day. To do or say noteworthy things every day involves some degree of forcedness, repetition, or trying. The opposite of authenticity.

If I wanted to get 10x more engagement than usual on a Tweet tomorrow, I could. I could post some celebratory brag about how much money I’m earning from my businesses (“omg $10k MRR!”). I could pick a fight on a topic people feel strongly about (“React sucks!”).

I could mention it’s my birthday and post a picture of myself (“Can’t believe I’m 41!”).

I could ask a question that lets people promote themselves (“What’s your favorite personal website?”),

angrily quote-tweet a terrible take, and so on.

I know these things work. And I occasionally do them, knowing they will work.

I try to do this only a handful of times a year, because even though they work, and even though they are useful for me and my businesses,

and even though they make my lizard brain feel good, a part of me still hates them. Even a few times a year.

Clearly I’ve been wrestling with this issue for a little while now.

But oh boy, not the people in my feed. The people in my feed—most of whom I’m not following, by the way—love posting for engagement. Some of them love it so much that they offer courses teaching other people how to do it—which amplifies this godforsaken death spiral even further.

And so now we find ourselves in a situation where all these asshats with 20k followers and a Stripe account are now running their Twitter account as a business. And this has led to a slow and inevitable decline from authenticity to some version of marketing (look at my content!) and sales (follow me!).

What we are witnessing now is the professionalization of Twitter.

And look, I don’t think it’s just the algorithm and the incentives. Elon’s political antics chased away a lot of good people.

Many of my favorite follows have moved to Mastodon, Threads, and Bluesky.

Also, more and more people are waking up and realizing that social media is actually quite bad for you, and leaving it behind.

Good for them. Bad for me.

Still—and quite ironically—if anything actually gets me to stop using this platform,

it’s going to be the changes that are supposed to make it grow.

If you liked this, you can share it on Twitter, discuss it on Hacker News,

or sign up below to get emailed when I post new stuff.

Notes