In 2017, I stepped down from my job as CTO of a 150-person software company to

see if I could make money selling my own software on the Internet.

Eight years later, I am now a full-time “solopreneur”—running a portfolio of revenue-generating software products

as a full-time job. I now set my own hours, take vacation whenever I want, and, amazingly, earn more than I ever did as CTO.

In the talk below, I’ll share how I did it and what I learned in the process.

I’ll share the skills that programmers should pick up in order to start selling software on the web, including both technical and non-technical ones.

I’ll discuss how to get started, evaluating your ideas, building your product, and getting your first users and customers.

The talk will draw from years of work building and selling software myself,

as well as the experience I’ve gained from helping hundreds of others launch their own businesses with SaaS Pegasus.

If you’ve ever wanted to turn your coding skills into revenue-generating side-projects, I hope this talk both inspires and helps you to get started.

TL;DR

Someone on Reddit asked me to provide a TL;DR for the talk. This was my off-the-cuff response:

- First you have to make space in your life for it. You need long blocks of time for deep work.

- The first idea you pick is unlikely to work, so pick something and start moving. Many of the best products come out of working on something else.

- When building, optimize for speed. Try to get something out in the world as quickly as possible and iterate from there.

- Pick a tech stack you’re familiar with, that you’ll be fastest in.

- Try to spend half your time on marketing/sales, even if you hate it.

- The most important skill you can have is resiliance. Not giving up is the best path to success. This is hard because there is so much uncertainty in this career path.

- It’s worth it! The autonomy and freedom are unmatched by any other career.

The talk

This talk was the closing keynote of PyCon South Africa on October 4, 2024.

It’s 30 minutes long, plus another 15 minutes of Q&A.

Alternatively, read on for an annotated transcript which I made using a process very similar to Simon Willison’s.

The transcript

I’m going to talk today about using coding skills to make passive income.

This email announcing the talk made me laugh, because the title does sound like clickbait.

Hopefully this is the non-clickbait version of this topic. I’ll leave it to you to decide.

First I have to explain my job.

“So, what do you do?”

Whenever I get this question I never really know how to answer it.

The most boring answer that I give is I’m a software developer, but I also run my own business.

If people know these words, I’ll say I’m a solopreneur or an indie hacker.

If I’m feeling really specific, I’ll say I run a portfolio of revenue-generating technology products, which is a bit of a mouthful.

If I’m feeling cheeky, I’ll say I make apps that make money while I sleep or… whatever I want?

How I actually earn a living is through a portfolio of technology products that are monetized online.

Basically that means I make stuff and I put it on the internet, and some of it makes money—either

through a one-time payment, a subscription,ads, affiliates, etc.

I have a bunch of different things that make varying amounts of money and every day I just kind of work on one of them,

support it, build a new thing, and so on.

Here’s how I got here:

Sorry, this slide had a lot of transitions and so the image doesn’t translate very well.

I started possibly like many of you in a normal corporate gig.

I didn’t last very long and I joined a friend’s company called Dimagi.

When I joined we were like three people and he was like ‘hey you want to be CTO’ and I was like ‘yeah I’ll be CTO’

and I basically larped as a CTO for a few years.

But the company became quite successful, and then before I knew it I was the CTO of like a 200-person company and I had like a 35-person team under me.

I was supposed to be a real CTO now, and I was, but I also kind of hated it.

I was doing all these meetings and management and I hardly ever got to write code.

And I eventually burnt out.

So I told my friend I needed a break. I decided to take like a six-month unpaid sabbatical

to figure out my life. On that sabbatical, I discovered this website called Indie Hackers

which basically is a website that told stories of people doing what I do now—building these random apps and making a living off them.

I thought “okay that sounds cool, maybe I’ll try that” and so I decided in those six months that I was going to try to earn

one dollar doing this indie hacker thing.

The first thing I did that succeeded was incredibly silly and I’m still kind of embarrassed about it,

but it’s basically an app that lets you make place cards—those little cards that you find at weddings and other events.

You upload a spreadsheet of your guests to this website, you download a PDF, you pay me like $5 (100 ZAR).

And I was surprised that it actually worked!

I made my first dollar and I was completely addicted.

It was this most incredible feeling and so then I tried to do it over and over again.

Eventually I thought “I bet other people want to do this over and over again too,” and so I got kind of meta and

built this product to help other people launch their own apps.

This is SaaS Pegasus—a configurable Django codebase that I now sell and how I make

probably like 80% of my money now.

Today, I’m blown away by how many people have built really cool products and really successful businesses on top of Pegasus code,

including YCombinator companies and also just random people’s hobby project that they’re doing with their friends.

It has over a thousand people using it, probably hundreds and hundreds of real products have been built with it, which is pretty fun.

Let me now clarify some key attributes of this path.

I’m talking about products, so the key thing is you’re not trading your time for

money—this is something that someone just buys and you get paid without having to do an hour of work for it.

I’m talking about monetized stuff. Passion projects are great, I love passion projects, but this is specifically

for people who want to replace (or supplement) their income.

I’m talking about bootstrapped, which basically means you’re not trying to raise money—you are trying to earn enough

from your own profits so you never have to raise money and you can take the profits yourself.

Finally, it’s a calm path—the goal is not to grow a 100-person company.

You could, but my goal was never to grow a 100-person company, it was just to have this kind of calm,

enjoyable life with lots of freedom.

A relatively mainstream term for this is indie hacking.

My goals for this talk are two: The first is just to kind of convince you that this is a possible career path that you can consider.

I think a lot of people don’t think of this as a career path, but it is.

And then if you decide that maybe you want to give it a shot, hopefully to give you some tips that help with your chances of success.

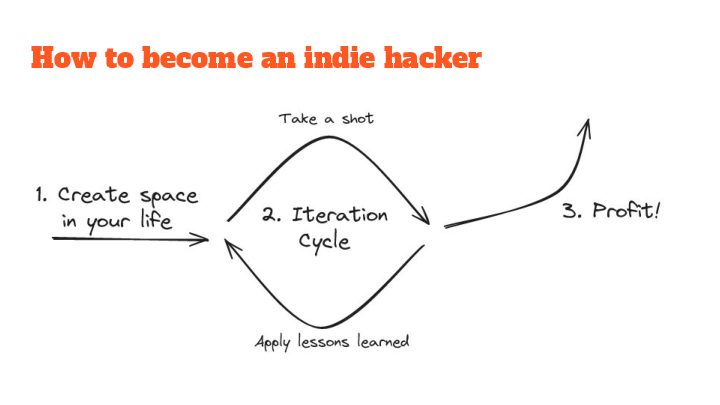

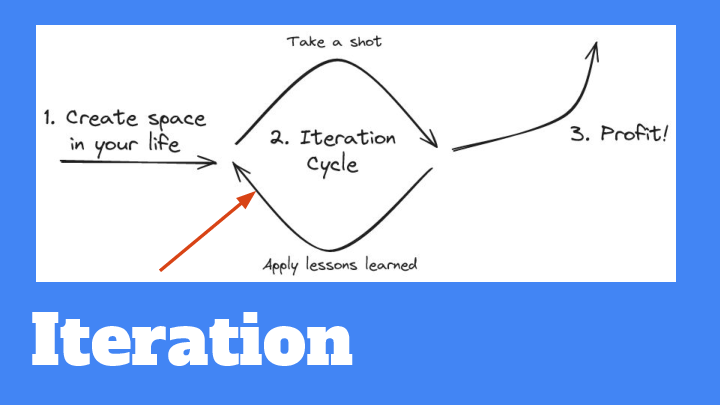

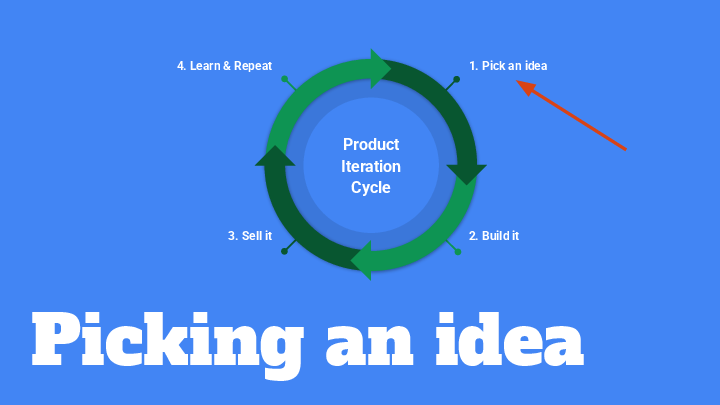

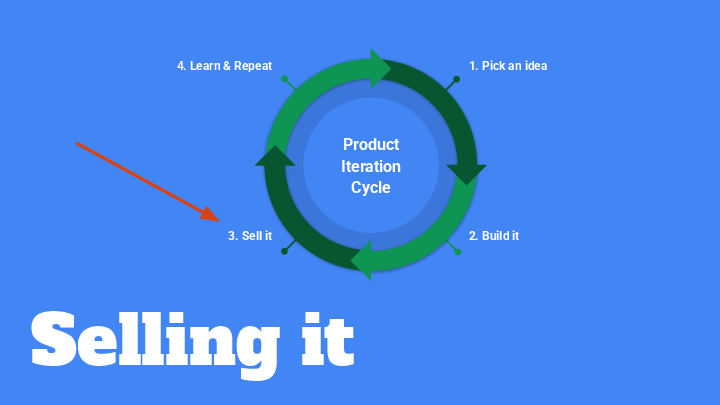

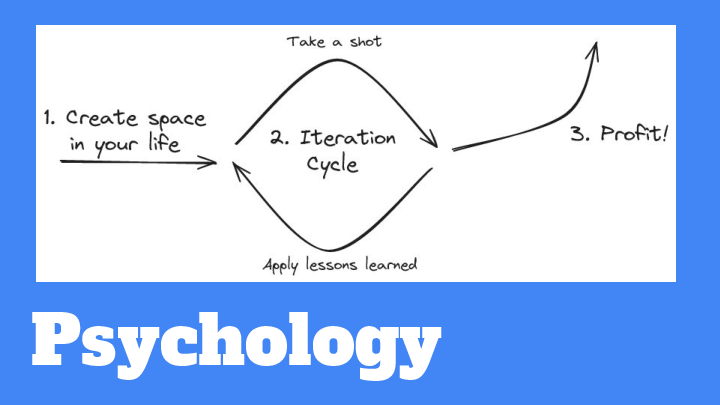

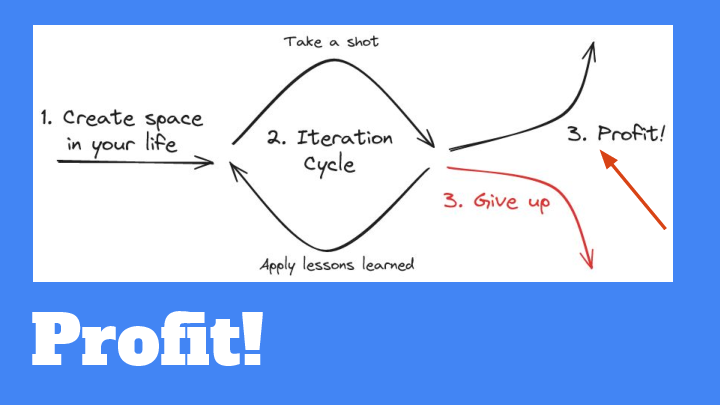

Here’s my diagram for how this can be achieved:

The first thing you have to do is create space in your life.

For a lot of people I think this is probably the hardest part—just finding the space to pursue something like this.

Then you enter this iteration cycle where you’re basically taking a shot at something,

and if it doesn’t work out you apply the lessons learned and take a shot at something else.

That doesn’t necessarily mean building a new product but could be trying a different approach to marketing,

trying a different way of presenting the UX, and so on.

Hopefully eventually something works and then you come out the other side and… profit!

Let’s talk about making space first.

So what do you need to get started?

The kind of boring answer is, basically, nothing!

Besides time.

And you need a particular type of time where you can do deep focused work on a consistent basis.

Which is not always easy to find.

So how do you make time?

I think the most common path is to fit it into your nights and weekends.

This is my friend Wisani who created an app called Boardroom

which is like Tinder for LinkedIn.

It’s growing pretty popular in South Africa and he’s got like 10 other projects.

He’s done all this while working a full-time job at Allan Gray and I think also getting an MBA.

Doing this at nights and weekends is definitely the least disruptive way to pursue this career, but it’s really hard.

For me, I have kids, I’m always tired at the end of a long day of work—this just wasn’t an option.

So what if you can’t pull this off?

Another option is to just kind of YOLO it.

This is where you quit your job and you’re like “cool I’m going to quit my job and I’ve got twelve months of savings in my bank account

and I’m just going to make this work.”

I think this is usually not a great plan—it puts so much time pressure and financial pressure on you to succeed.

And there’s just so much variance—it’s not like if you just work your butt off for a year you’re guaranteed to

succeed in ways that some jobs are more like that.

What I did, and the path that I recommend, is more of just a patient thing where basically you try to integrate

this quest into your regular life in a slower and more sustainable way.

Typically that means working less, and therefor either earning less—you ask your boss if you can have Fridays off and get paid 80% as much—or

getting paid more per-hour by switching to contracting or freelancing.

Then you build some products and basically whenever those products start earning, you can sort of re-adjust the hours until it works.

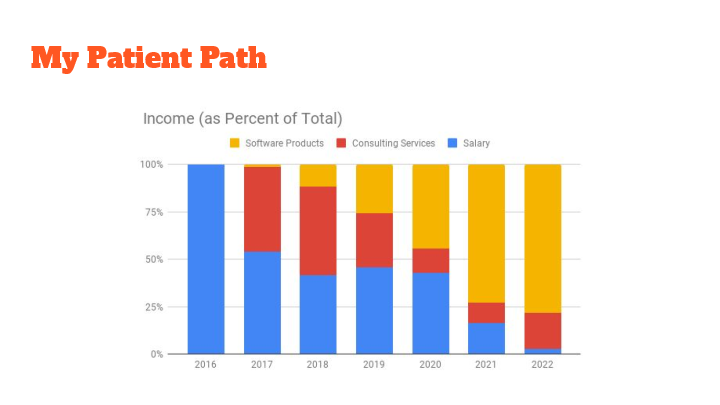

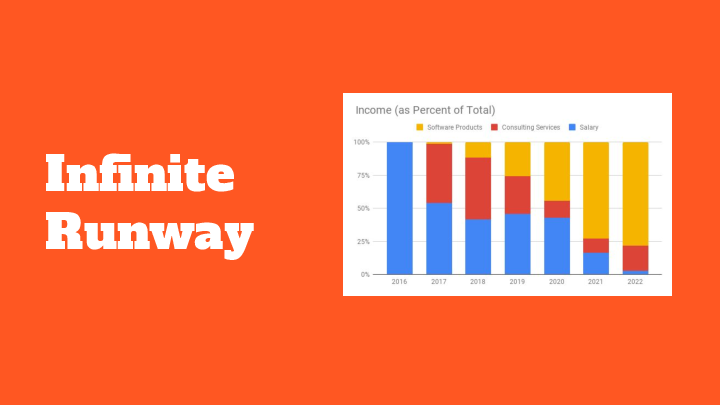

This is my actual income for my first seven years on this journey:

In 2016 I was a full-time employee.

In 2017 I went on sabbatical and started doing this thing and I dropped down to halftime at my job and filled most of my income with consulting.

I just tapped my network and said “I’m available, I’m going to charge a lot”. And thankfully, some people said yes.

There’s this tiny little sliver of yellow there and that’s me selling those place cards.

But basically what happened is that it was like a snowball that feeds off on itself and so year two I made a bit more,

year three I made a bit more, and I eventually dropped down most of my consulting and then I finally quit my job.

Obviously this took a long time, but the nice thing was that I was never stressed out. There was never any financial pressure on me.

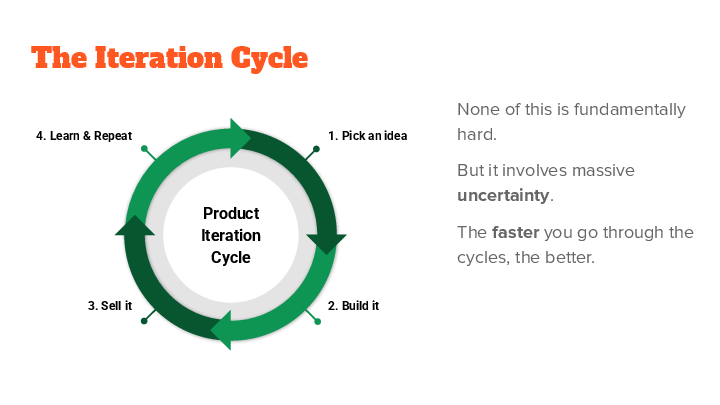

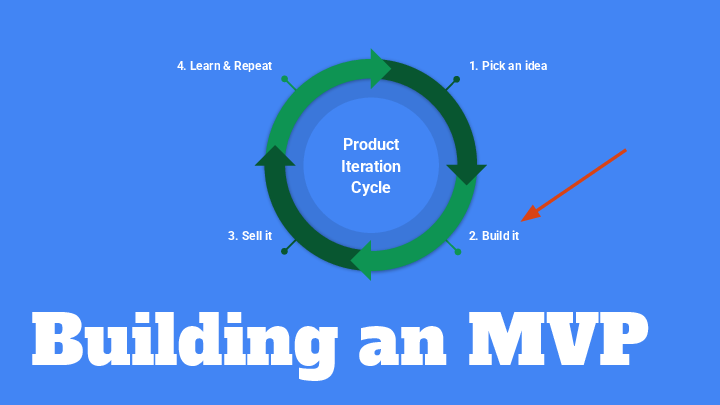

Now I’m going to jump into the main iteration cycle.

I want to zoom in on what this looks like.

It’s a simplification but basically you pick an idea, you build it, you sell it, and then you repeat.

Going back to the “anyone can entrepreneur” thing—none of this is fundamentally hard; it isn’t rocket science.

If you can teach yourself how to code you can teach yourself how to market, or how to validate ideas.

This is all stuff you can learn.

But it involves massive uncertainty.

What that means is you want to go through the cycle as much as possible because on any given iteration you don’t know what the outcome is going to be.

If you spend your first two years building a product and then come out the other side and realize nobody liked it, then you’ve wasted a lot of time.

Whereas if you can figure out the product is flawed in two weeks or two months then you can go through the cycle a lot faster (and many more times).

I like to think of myself as a one-person venture capital portfolio.

A VC fund will typically invest in 100 companies and they will expect 90 of those companies to completely fail.

But, if they find the next Facebook or the next Uber then everyone who invested in the fund makes tons of money.

I think you should think of yourself in the same way where you want to take as many shots as you can on goal, hoping that one of them succeeds.

Obviously you’re not going to be the next Uber, but you’ll start making $10, $100, and then eventually you can direct your energy into that project and grow it.

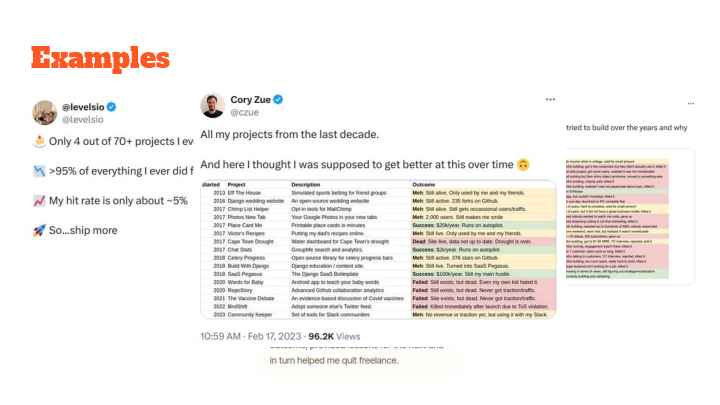

Here are some examples from the indie hacking world about this:

Sorry, this slide also got mangled by the transitions.

Pieter Levels, who just sleeps in vats of money, says his hit rate on projects was about 5%.

But that was still enough for him to have this incredible career doing a very similar thing to me.

There’s this guy Rob Hope who is a South African—he’s got this project graveyard

on his website where he documents all the things he’s tried that have failed.

Another example from Twitter, this guy Pat Walls published his failures,

and I stole his format and published my own version.

Basically you can see I’ve done a lot of these things and only a small number of them have actually worked out.

So a lot of things going to fail, and therefore you want to go through them as fast as possible.

Let’s look at picking an idea.

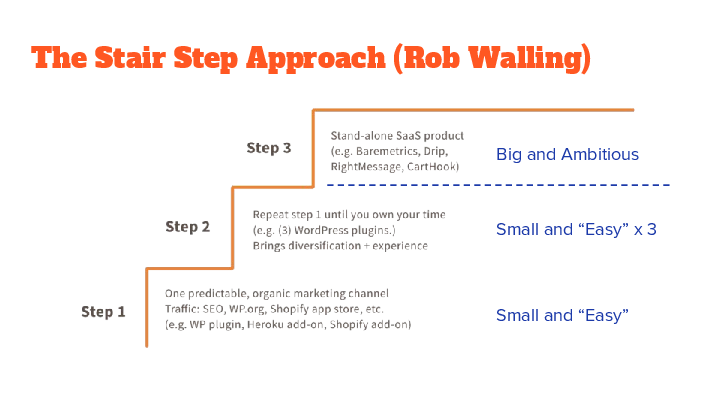

This is a diagram that I borrowed from a successful entrepreneur named Rob Walling.

The key here is basically you want to walk up these steps of difficulty.

You want to start on step one with the smallest, easiest possible thing that you can do.

For me, that’s like someone can give me $5 to buy a PDF of placecards—that’s a very easy thing to build, and a very easy thing to sell.

Once you do that, then you try to do it again, and again, and eventually if you are successful then you kind of own your own time.

That’s step 2.

Rob’s step three is to go do a big ambitious thing.

I drew a dotted line there because you don’t have to go to step three—you can just have a bunch of step two projects and be

having a nice life as a developer with a lot of freedom.

Go take a moonshot if you want, but you can just do stuff in step two and I recommend that too. That’s kind of where I’ve landed.

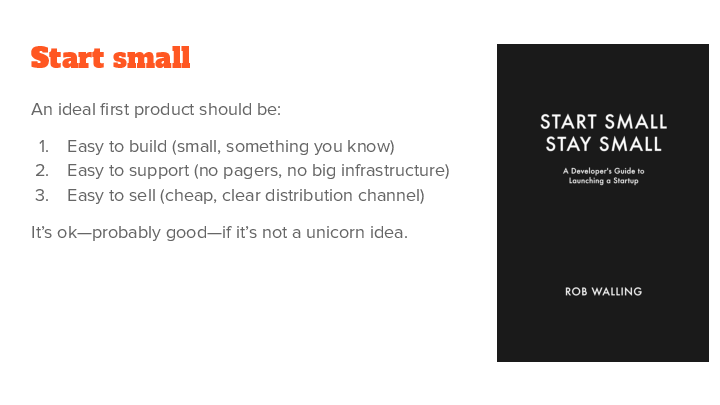

Start small is the key in terms of thinking about ideas.

Your ideal first project should be easy to build, easy to support and easy to sell.

And it’s actually good if it’s not a unicorn idea.

Don’t try to build the next Facebook or Uber or OpenAI or whatever else—you want to find a really specific niche and go in there.

So how do you come up with ideas?

There’s lots of stuff you can read on the internet about this by people who know and see a lot more than me,

so I’m not going to give specifics apart from saying just go do something!

Using an example from my own life:

I got married, we had this issue where we had to print these stupid place cards that led to me building this place card application and that was my first thing.

Then I was building these applications and I was like “oh that’s another problem” so then I built SaaS Pegasus.

Then I had this SaaS Pegasus community that I was trying to support and I kept answering the same questions over and over again so

I thought “oh I’ll build a RAG chatbot.”

Through building something I found a new problem and then I could go build something else.

Don’t do something just because the first thing you’re going to pick is going to work,

but do something because by doing something you’ll just get exposed to more stuff and then that will lead you somewhere interesting.

Just keep following interesting problems until you find one that you want to solve.

I want to quickly mention this book “The Mom Test” which is a great book about idea validation.

The key point from this book is when you’re trying to pitch a startup idea to anybody, they’re going to talk to you like your mom would talk to you.

You’re going to pitch your thing and they’ll say “sweetie that’s such a good idea, I love it, you’re going to be so successful.”

People do this because they don’t want to burst your bubble.

You’re coming to your friends, you’re coming to your co-workers saying “I got this cool idea for an app”—no one’s

going to tell you that idea sucks, because they want you to not have your confidence destroyed.

This is a really good book that hammers that concept home for you and then gives you a framework for trying to get around

the fact that everybody’s kind of lying to you when you pitch your ideas.

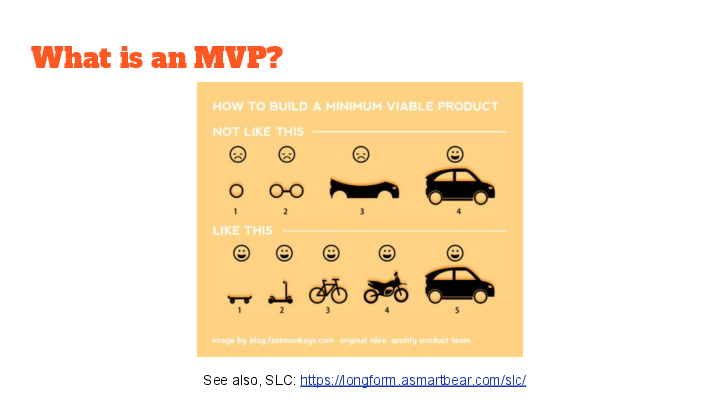

Now I’m going to talk about building and specifically building an MVP—a minimum viable product.

Probably a lot of you have heard of MVPs.

Basically it’s like you’re trying to build the smallest, useful version of your thing.

In this example, a skateboard is useful—you can ride a skateboard and get from point A to point B,

whereas if you have a wheel of a car or an axle of a car, that’s not useful.

There’s also a concept called an SLC which stands for simple, lovable and complete, which I really like.

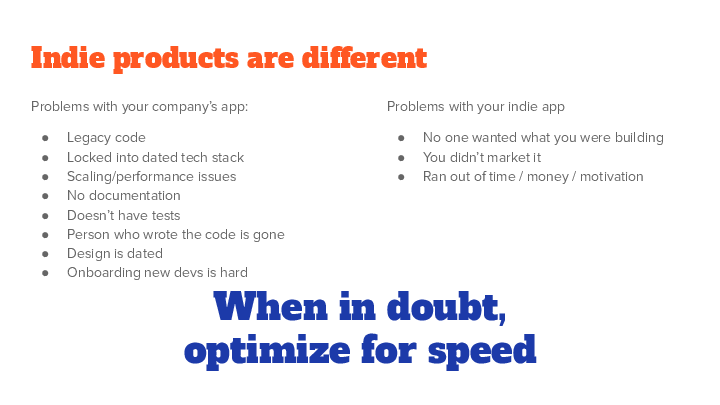

Before we talk about MVPs, let’s talk about why indie products fail.

Why do indie products fail?

The main thing I want to emphasize here is indie products are different from most big company software that probably a lot of you have worked on.

In traditional day jobs at places like Amazon, you’re probably dealing with legacy code and maybe the person who wrote

it left and there’s no documentation and there’s all these scaling issues, performance issues—and none of this matters in the indie world.

If you’re building independent projects, the reason that you’re going to fail is no one wanted what you were building,

you didn’t market it, or you ran out of time, money and motivation.

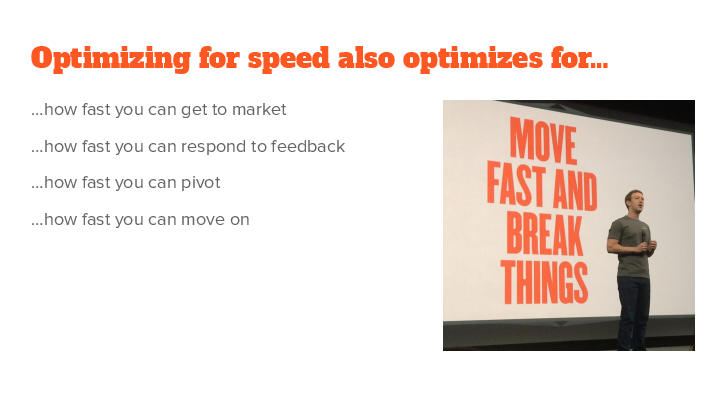

The takeaway is just when in doubt, optimize everything for speed.

That optimizes for how fast you can get to market, how fast you can respond to feedback, how fast you iterate,

and how fast you realize your idea was really dumb and you should go do something else.

I’m not saying write a bunch of terrible code—I’m just saying be smart about it.

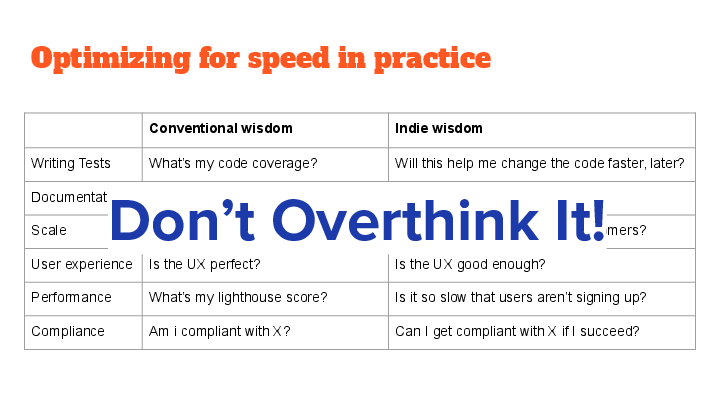

Taking something like tests—you shouldn’t care about code coverage or anything like that.

What you should care about “is if I write this test, am I going to be able to modify this code more confidently faster later?”

If so, do it. If not, maybe don’t worry about it right now.

In other words: “Don’t overthink it.”

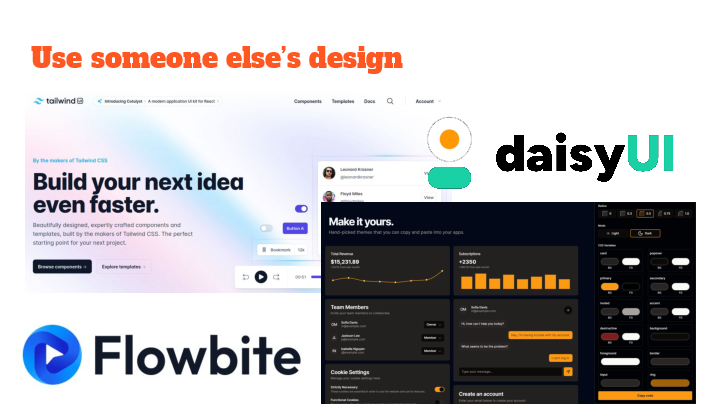

Now let’s talk about design.

Design is often the weakest spot for developers and it certainly was for me.

Thankfully, you don’t really have to be a designer to make good-looking things anymore.

There are all these different open source and paid templates where you can just get these really beautiful designs that work

on all screen sizes and they have component libraries you can just drop everything in.

You really don’t have to do any design—you can just steal other people’s designs and I recommend doing that again just

because it’s faster and because you can make it beautiful or unique later.

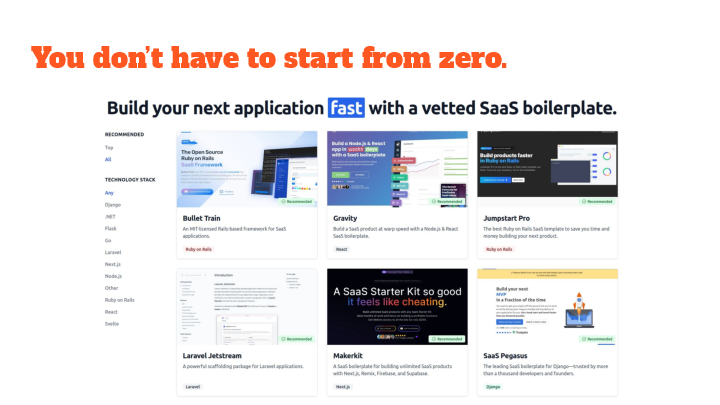

Also, you don’t have to start from zero.

This is a bit of a shameless plug but it’s also the case that I’ve seen a lot of people use products like SaaS Pegasus

(mine) to launch their products way faster.

They are called SaaS boilerplates, or

SaaS Starter Kits.

It’s a whole product category with both open source, free and paid options.

These projects often have a ton of stuff built for you.

Then, instead of your first two weeks just being “okay I’m going to build user accounts and I’m going to build billing and I’m going to build multi-tenancy”

and all this stuff, you just have all that ready to go and can focus on the one thing that you need to do.

Ok, big question: what tech stack should you use?

There is a right answer to this.

The answer is: the one you know.

If you want to learn a new tech stack as a fun educational project that’s great,

but if your goal is to get this revenue-generating product in the world,

you want to be working in something you’re familiar with because you want to be as fast as possible.

If you don’t know anything, just pick something popular.

Popular things have the best communities, best documentation, the language models are the best at working in them and so on.

I use Django, HTMX and Tailwind for most of my stuff—I like it but you should do what you know.

And remember, if you’re not embarrassed by the first version of your product, you’ve launched too late.

That’s a quote from the founder of LinkedIn.

This was the landing page for Place Card Me that I used for the first year or something like that.

Those are literally font awesome icons and just this giant stupid button.

You have to get comfortable putting things out into the world that don’t meet your level of internal quality because you just have to try it.

Starting the feedback loop is much more important than building a perfect thing.

Let’s move on to selling.

I think one of the biggest fallacies that I see in developers is this idea that if they build the best product in the world,

they’re going to be successful.

They think the reason that some software is successful is because it was the best product,

when usually it is because that product had the best marketing team or some combination of a great product and great marketing.

An uncomfortable truth is that you will need to spend a lot of time selling your product through marketing or sales.

There’s this book “Traction”

that I recommend, which is where I got the takeaway that I should be spending half of my time on marketing and sales.

I think of it like eating my vegetables—I love coding, I hate marketing.

It’s like “I have to do marketing today” and it’s like eating my vegetables before I can have my french fries.

I also recommend selling your product before it’s ready.

I’m sure we’ve all had this experience where you find some app that looks really cool and you want to sign up,

and then you just get this popup asking for your email address.

As a consumer, that’s super frustrating, but as an app builder this is really useful for two reasons.

One reason is that if you can’t get someone to give you their email address, then it’s going to be very hard to get them to pay you.

It’s a good proxy for whether you’re building something that anyone is even remotely interested in.

You put this up, figure out a way to drive traffic to it, and get a bunch of emails - that’s a good sign.

If you drive a thousand people to this website and don’t get any emails, that’s a bad sign.

It’s also really important to have people to tell about your product when it’s actually ready.

What often happens is someone will build in the darkness for a long time, they’ll launch their product,

put it on Hacker News or something, nobody notices, and then they think that they failed.

But they haven’t failed, they just had unrealistic expectations of success.

If that person instead had a list of 200 people that they knew were interested in their product,

then before launch they could email 20 of them and set up Zoom calls to walk through it and get feedback.

You can iterate there, email the next 20, and so on.

Then when you actually launch you email the whole list.

Hopefully you have people jumping into your product from day one, and it’s better than it would have been otherwise.

Let’s talk about getting your first traction.

These are some strategies that worked for me.

Communities are a really good place to find early users.

The great thing about communities is they’re incredibly niche.

If you’re building a product for plumbers who play Dungeons & Dragons, there’s probably a Reddit for that, probably 20 Facebook groups for that,

and you can go immediately into those communities and talk to your ideal customer profile.

One thing to know about communities is that all marketers use them this way, so communities hate marketers.

They develop a pretty strong immune systems towards people doing marketing stuff.

So go into communities tactfully, be nice in the community, add value, and mention your product when it’s relevant.

This is a great way to find early users.

Ads are another good way to find early users. Google sponsored links are very prominent, and you can use ads on tons of other platforms.

Ads are great to try to answer that question of whether anybody wants what you’re building or if anyone can figure out how to use your product.

You can just pay a bit of money for a hundred people to come play with your website and figure out what’s happening.

I don’t recommend using ads as a way to make money—you will lose money on this exercise (at least in the beginning)—but

you’re essentially trading early bits of money to do some user research.

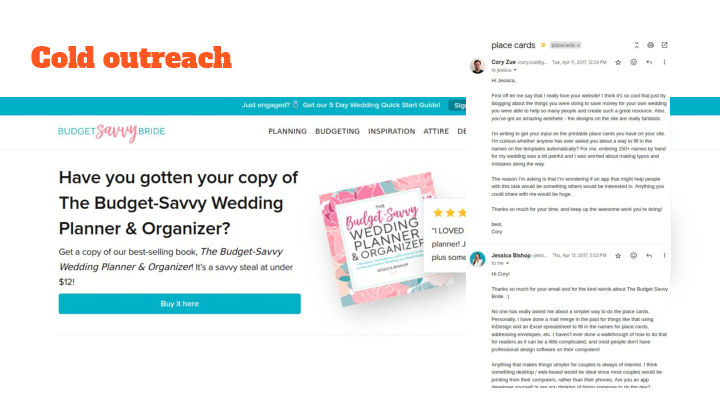

Cold outreach is another uncomfortable one that also works sometimes.

When I was building Place Card Me, I spent an hour a day just reading wedding blogs and writing long personal emails to wedding bloggers.

I would do this every day and most of them never responded to me, but one of them did.

This person helped me tremendously in terms of teaching me about the industry, gave me backlinks on her site,

and gave me some place cards designs.

Cold outreach can be a good strategy, though it’s getting harder in the age of AI spam.

It’s better to write one really good email or Twitter DM than to find some tool that uses an LLM to write a hundred terrible ones.

Content is my main way that I market my stuff today.

Basically, if you’re building a product for a specific industry you create content that’s useful for that industry.

I target Django developers, so I write content about Django.

Then people who are Googling how to deploy Django or

how to connect Django to Stripe find my guides,

and that’s a nice way to get exposure to my product. You get backlinks and so on.

I do some of this stuff on YouTube now also. Video is huge—I don’t have really any YouTube following but it still drives a good amount of traffic.

This is something that you can do as an individual, just writing these blog posts or recording little screencasts.

I hesitated to put this slide on, but this was something that I did a lot which is called “building in public”—that’s

just where you share what you’re working on publicly. I did this on my blog.

You’ll see this on Twitter all the time; it’s gotten to be a very noisy channel.

But the nice thing about this strategy is it requires no work.

You just work on your project for two hours and then post a screenshot of what you did.

Maybe a few people will find what you’re doing interesting, follow along your journey,

and then they become little advocates that will try your products or connect you to other people.

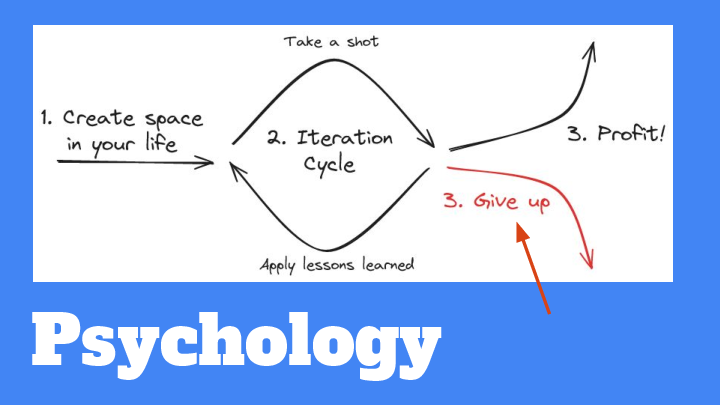

Now I want to talk a little bit about psychology.

I lied with this diagram—this is not the only thing that happens.

There’s another path which is not as good: giving up.

Courtland Allen, who is the founder of Indie Hackers, interviewed hundreds of people who have gone down this path.

When asked what his biggest takeaway from the success stories was, he said all you have to do is just not quit.

There was no other generalizable advice he had—just don’t quit.

So how do you prevent yourself from quitting?

One way is by having infinite runway, which I talked about already.

Setting things up so that money is not the reason you quit is a good way to eliminate that particular constraint.

You still might run out of motivation, though.

In order to stay motivated, I think one of the most important things to do is to just manage your own expectations.

I like this quote from Bill Gates: “Most people overestimate what they can do in a year and underestimate what they can do in 10 years.”

This really resonated with me. If you think “I’m gonna go down this path and take a shot and spend three months and launch my app”

and then it didn’t work so you quit—that happens to a lot of people.

Instead, if you think of it as more of a five-year journey or a ten-year journey,

you’re just going to take these really small steps that don’t really look like they’re working, but they’re cumulative and eventually they add up.

Embracing learning is another important one.

This is kind of like a Dungeons and Dragon’s character skill chart—probably the average person in this room is a pretty good coder,

maybe knows a bit about product and marketing and other skills.

But in order to really succeed in this career, you have to look more well-rounded.

The hard part is really just embracing the idea that you’re going to learn these skills that don’t feel comfortable.

I’ve never enjoyed marketing or wanted to be a marketer, but it was something that I had to learn in order to sell stuff.

If you’re not willing to get outside your comfort zone and learn things that are outside what feels comfortable,

you will probably have trouble.

Finally, be resilient.

This is a funny graph showing how much money I was making every week on Place Card Me in the beginning of 2020.

Things were going great—I was making up to $400 a week, and then all of a sudden there was a global pandemic

and people weren’t having weddings anymore. My primary source of passive income just dropped to zero overnight.

That’s just one example of things that happen to you because this is a very unpredictable career.

The highs are really high, the lows are also really low, and you have to be resilient to these ups and downs.

Going two weeks without earning any money and then one day a bunch of money appears in your bank account, it’s a very stressful thing.

You have to get used to these big swings that you just don’t have in a salary job.

But if you emerge on the other side, hopefully you can profit.

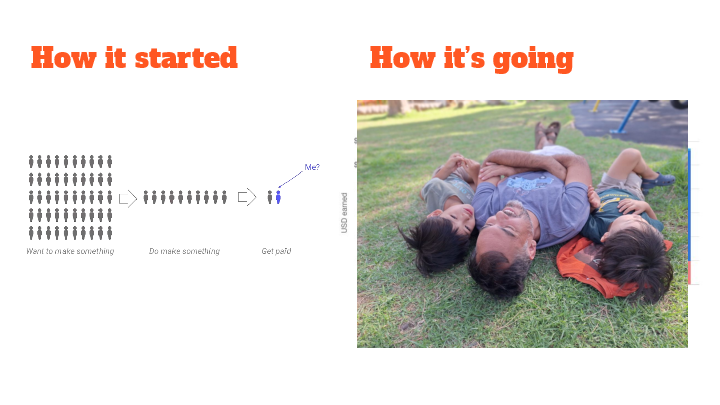

This is from my very first blog post when I first started - I just wanted to get someone to pay me a dollar on the internet.

That was my goal.

Eight or nine years later, I am making more money than I ever made as CTO of my company.

But more importantly, it’s a very nice lifestyle.

I have time to hang out with my kids whenever I want, I can go on long vacations, nobody tells me what to do,

I can take meetings whenever I feel like it (or never).

So yeah, I recommend this career.

And if it sounds interesting, I recommend you give it a shot, and see if you can make it happen.

Thanks for getting this far!

If you liked this you can comment below, share it, or subscribe to get email updates when I publish new stuff.